The Nebraska Federal Writers’ Project: Remembering Writers of the 1930s, Part 1F – Meeting Lowry Wimberly

By 1932 times were hard and getting harder. With so many destitute men on the road, competition for day labor and other temporary jobs intensified. The romantic travels of Box Car Rudy Umland had to come to an end. Umland returned to the family farm near Eagle to slop hogs, plow corn and “fight drought, cinch-bugs, depression and dust storms on the farm.” At the same time, Umland set out to write a memoir of his travels. When he gave a part of the manuscript to Kenneth Forward, who had been his English instructor at the University, Forward told him he needed to meet Lowry Wimberly.

Lowry Wimberly was at that time already an almost mythical figure–the Greek god, Umland joked, of the local literary scene. Wimberly was the founding editor of the Prairie Schooner, widely acknowledged, from its first appearance in 1927, to be among the leading literary magazines in the United States. He was witty, gifted with a sardonic sense of humor, and, above all, he possessed a memorable persona. His enthusiasm for writing was contagious. He enjoyed an informal sociability with his writers that helped transform Lincoln in strange and surprising ways.

Mari Sandoz later told Umland that she believed that Wimberly had reawakened a literary consciousness that had been dormant in Lincoln since the 1890s. She recalled the decade as one in which a certain “bohemianism suddenly took root and flourished” in Lincoln. Other writers felt the same. Loren Eiseley recalled “a certain magical quality in the air” in the Lincoln of those years in a letter to Umland written many years later. Umland himself compared the atmosphere of Lincoln at that time with that of Greenwich Village, with people in every cafe discussing books and writers.

Umland’s meeting and subsequent friendship with Wimberly changed the course of Umland’s literary career. First came an association with the Prairie Schooner. “I am meeting you” Wimberly told Umland, “just when I am losing Alan Williams as the business manager of the Schooner.” Wimberly believed that coincidences were never accidental. Umland worked for the Schooner in this–naturally unpaid–capacity for several years. In that first meeting, the two also discovered that they “shared the same birthday, had slept in jail, and liked Chaucer’s ‘Miller’s Tale.'”

In Wimberly, Rudolph Umland met someone who would become a close personal and intellectual friend. Months later, Umland would meet Mari Sandoz for the first time in Wimberly’s office. Wimberly introduced Umland to wider and more sophisticated literary circles. Umland began to meet people who would offer him intellectual stimulation, moral support, and useful criticism. In the same year, 1934, Wimberly published Umland’s “Sandhills Interlude,” in Prairie Schooner. It was the first of many Umland stories to appear in the Schooner. It drew on a rich knowledge of the American social and cultural landscape that Umland accumulated during his years as a “hobo.”

Umland’s style of writing changed. He had wanted, when he was riding the rails, to write like Dostoevsky or Chekov. That was, he said, his “Russian Period,” and he wrote “gloomy pieces about social injustice… death and similar miseries.” Now, though he wrote about hard times of drought and depression, and about the struggles of old settlers, his generous sense of humor kept him honest. He respected his subjects too much to paint their lives as dark unremitting tragedy. He found in keen observation of their character, their speech, and the detail of their work and daily lives, a spirit too individual to be reduced to such a scheme. And in this individuality Umland often discovered the spark of comedy, a wry humor often shared by the inhabitants of the Great Plains. His best writing for the Schooner in the years following would be in this vein. His article “Phantom Airships of the 1890s” (1938), perhaps his most widely noticed Schooner essay, is a fine example of this genre of serious but still gently humorous non-fiction.

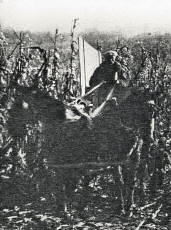

The Umland farm felt the deepening impact of the depression throughout the early 1930s. In his scrapbook, next to the picture at right, Umland wrote that “Herbert and I raised over 4200 bushels of corn on our father’s farm in 1933, some of our fields producing 80 bushels an acre. The price of corn fell so low that we decided to keep most of it and feed it to hogs the following year. We raised 300 hogs in 1934 but had drought and the market became glutted with hogs. Young pigs sold at livestock auctions for as little as forty cents a dozen. The hogs we raised ate up the previous year’s corn and brought us no profit.”

In 1935, Umland’s brother Herbert got married and his parents retired from the farm to a house in nearby Eagle, Nebraska. After working over the winter as a farmhand, and viewing his economic prospects with some despair, Umland decided to become a hobo once more. He stopped in Lincoln to say goodbye to Lowry Wimberly and leave him another manuscript for the Schooner. Wimberly, however, seemed troubled by this news and replied “You can’t leave Lincoln now… it’s too damn cold to ride in a box car.” He told Umland about the new WPA Writers’ Project, housed in the Union Terminal Warehouse just a couple of blocks from the University. Wimberly accompanied Umland to a job interview with the Director of the Nebraska Project.

Umland got the job. Wimberly was undoubtedly a forceful and effective patron. Nevertheless, Umland was surprised and bemused by the turn of events. “I had never done any editorial work,” Umland recalled, “but it was apparent that the director of the project was even less qualified for her position because she immediately hired me.” Umland credited Wimberly with starting him on a career of government service that would “keep me forever out of boxcars and cornfields.”

Contact Us

Lincoln City Libraries

136 South 14th Street

Lincoln, NE 68508

402-441-8500