The Nebraska Federal Writers’ Project: Remembering Writers of the 1930s, Part 2B - Nebraska Beginnings

The Nebraska Federal Writers Project, like every other state’s Federal Writers’ Project, began in 1935 with the announcement of federal funding and the appointment first of a state WPA administrator to set up and supervise the financing of the program and then of a Project Director to begin hiring and actually supervise the work. But this bureaucratic history misleads us. The Nebraska Project that really unfolded from this impetus had origins that reached back into the 1920s and intertwined with the origins of the Federal Project.

The 1920s had been a decade of profound literary disillusionment. From the publication of Sinclair Lewis’s Main Street in 1920, American intellectuals struggled with their dislike of the enforced conformity, mindless boosterism, and cultural poverty of small town America. The rebels of the 1920s were contemptuous of religion, hated the provincialism of American culture, feared industrialism and mass culture, and did not really believe in an autonomous American culture. They looked abroad, and often moved abroad, to France, to find sophistication and real culture. The title of H.L. Mencken’s first magazine, The Smart Set, was the unhappy expression of the elitism and arrogance that fed the fashion of disillusion. Mencken’s immensely influential American Mercury, which began publication in 1923 retained many of these prejudices.

When, in 1931, the historian Fredrick Lewis Allen looked back at the preceding decade, the title of his book, Only Yesterday: An Informal History of the 1920s played on the great gulf in feeling and the imagination that now separated American intellectuals from things they had said and felt only a short time ago. Allen read Walter Lippmann’s biting description of the rebels’ disillusionment with their own rebellion, and observed that aimlessness fully experienced must fade. He noticed that when expatriates of the 1920s ran out of money and returned from Paris, they took up native themes. He observed how the exceptional quality of American literature had freed it from the assumption of American inferiority. He cited Cather’s novels among works by Sinclair Lewis, Theodore Dreiser, Stephen Vincent Benét and Hemingway as fully realizing the promise of a uniquely American literature. Allen took note of a new interest in American folklore, and saw that Mencken, in offering vigorous praise of honest American writing, had stimulated the creativity of American writers.

In just a few short years, disillusionment retreated. A more determined spirit took hold, founded on the conviction that American culture, emerging in a diverse array of regional and ethnic folk cultures, was autonomous, creative, and of great value. This spirit of optimism was to be one of the great paradoxes of the depression years. In years of relative prosperity, literary intellectuals had burned through their disillusionment, and found new respect for American culture and for ordinary people. They discovered that their country was more diverse and interesting than they had believed.

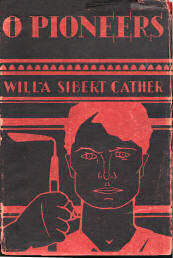

The work of Nebraska writers guided, informed and enlarged this new sense of purpose. Willa Cather’s novels and stories about ethnic immigrants on the Great Plains portrayed their vitality, their strength of character and their thirst for culture, as well as their conflicts with Protestant, Anglo-Saxon “American” settlers. Cather recorded a historical moment in which, traveling from one Nebraska town to another, one might find Czech, Norwegian, Swedish, French or English the predominant language. Her honest portraits of this diverse world and its conflicts revealed the importance of culture and language in new ways. Her work showed how different folk-cultures mixed and conflicted to weave the complex cultural fabric of life on the plains. Her respect for ordinary people and her studies of the complex communities of the plains frontier pointed in a very different direction from the scathing criticism of small town America by writers like Sinclair Lewis and H.L. Mencken.

The work of Nebraska writers guided, informed and enlarged this new sense of purpose. Willa Cather’s novels and stories about ethnic immigrants on the Great Plains portrayed their vitality, their strength of character and their thirst for culture, as well as their conflicts with Protestant, Anglo-Saxon “American” settlers. Cather recorded a historical moment in which, traveling from one Nebraska town to another, one might find Czech, Norwegian, Swedish, French or English the predominant language. Her honest portraits of this diverse world and its conflicts revealed the importance of culture and language in new ways. Her work showed how different folk-cultures mixed and conflicted to weave the complex cultural fabric of life on the plains. Her respect for ordinary people and her studies of the complex communities of the plains frontier pointed in a very different direction from the scathing criticism of small town America by writers like Sinclair Lewis and H.L. Mencken.

Equally important in shaping an alternative to the disillusionment of the 1920s was the influence of Louise Pound. Pound, who taught in the English Department at the University of Nebraska from 1894 to 1945, was a founding editor of American Speech. She led the way to the linguistic study of living language, and to the scientific study of American folklore. She served as president of the Modern Language Association and of the American Folklore Society. H.L. Mencken mentioned her twice in the introduction to his 1919 The American Language, and credited her with “putting the study of American English on its legs.” She set the study of folklore on firm empirical foundations and helped establish the diverse sources of American folklore against the prejudice that Anglo-Saxon lore alone was American.

The best work of Willa Cather and Louise Pound described a regional America. They both discovered a living American culture woven together from ethnic, national, and regional cultures. The vitality of the American culture Cather and Pound described contrasted starkly with the emptiness Sinclair Lewis portrayed in Main Street and the ignorance of H.L. Mencken’s hated “booboisie.” Cather and Pound’s realistic portraits of culture as a diverse and conflicted reality in the lives of individuals and communities, their appreciation of how individuals created stories and lives from cultural materials, and their eye for telling detail pointed toward a view of America that coalesced in the emergence of literary regionalism in the 1930s.

Regionalism grew into a national movement that reshaped the literary and artistic scene of 1930s America. It absorbed all the energies and ideals that rejected the disillusionment of the 1920s. It replaced disillusion with confidence in the unique value of American culture and American achievements. Regionalists promoted a cultural nationalism that was self-consciously very different from the ugly cultural nationalisms of contemporary fascism, nazism and communism. Schooled in the real regional, ethnic, social and racial heterogeneity of American life, regionalists rejected simplistic ethnic or religious definitions of American identity. They promoted a pluralistic nationalism, urging Americans to take an interest in their own ethnic and regional history, in folklore and local traditions. They believed that as Americans came to know more about their own local history and traditions, they would encounter and take an interest in the contrasting traditions of their neighbors and fellow citizens. Regionalism would widen and deepen the sense of community necessary to sustain democracy.

As a national movement, regionalism had many midwives. Artists John Steuart Curry, Thomas Hart Benton, and Grant Wood gave the idea broad public currency. Mencken contributed through his study of American dialects and through his book reviews. Jerre Mangione recalls writers Van Wyck Brooks, Randolph Bourne and Lewis Mumford as especially influential. Franz Boas, historian Jerrold Hirsh shows, was also an important contributor.

Among this impressive galaxy of thinkers, Nebraska’s writers, from Cather and Pound on, wielded powerful, sometimes decisive influence. If Mencken is in the list, we remember his acknowledgement of Louise Pound. If the list begins with John Stueart Curry, Thomas Hart Benton and Grant Wood, we remember Rudolph Umland observing how Lowry Wimberly’s Prairie Schooner played an equivalent role in bringing national attention to the unique culture of the Midwest. Wimberly built Prairie Schooner into one of the most widely admired and influential literary magazines in the country as a regional magazine. When Wimberly turned to writers distant from his own region, he still chose writers whose work fit the regionalist mold, among them the young Eudora Welty, August Derleth, and Jessamyn West. Mari Sandoz, still struggling in 1935, about to gain recognition for her unique understanding of the cultures of the Great Plains, would soon demonstrate the power of a raw but authentic regional voice.

The Impact of Regionalism

Regionalism made the Federal Writers’ Project possible. Neither the alienation and cynicism of the 1920s writers, nor the radicalism encouraged by the Great Depression could have been supported by a politically viable federal program. The cynicism of the 1920s and the radicalism of the 1930s pointed to truths about American society, but suffered from narrow perspectives, superficial moralizing and elitism (no one could be more elitist than the self-authorized representatives of the proletariat). Regionalism adopted a more fruitful and creative set of concerns. The regionalists wanted above all to document the diverse regional and ethnic cultures of the United States and their practices. They would be prodigious collectors of traditions, oral histories, folk music, folklore, life histories, and slave narratives. Their democratic project, as Benjamin Botkin put it, was to “let people speak in their own voice and tell their own story.” Regionalists’ respect for the way ordinary people draw from and create culture made them optimistic about the future. Where they found injustice, they believed that as people from different social and ethnic groups told the stories of their contrasting experiences of American history, they would build the mutual respect and informed judgment necessary to support reform.

The rapid advance of this perspective was the striking cultural surprise of the 1930s. Jerre Mangione, grown close to writers who built regionalism into a national movement while working as an FWP administrator in Washington,D.C., found it “one of the most striking anomalies of the Great Depression… that, while the gospel of Marx and Lenin was rapidly drawing converts” there grew a “strong movement to understand and interpret the American ‘character,’ which had been almost totally ignored until now.” Even the Communist Party, he noted, rewrote its slogans to reflect the emphatic “Americanism” of this movement.

The productivity and quality of work achieved by the Nebraska Writers’ Project and its smooth relationship with the Washington Administration of the Federal Writers’ Project reflected shared history and shared commitments. The influence of Lowry Wimberly, his Prairie Schooner, Mari Sandoz, Addison Sheldon of the State Historical Society, and Louise Pound nurtured a sophisticated interest in folklore, local history, the natural world–all aspects of the disciplined realism of the regionalist paradigm.

In 1938, Benjamin Botkin, who had come to study linguistics and folklore with Louise Pound at Nebraska in the late twenties and early thirties, became national folklore editor for the Federal Writer’s Project. Botkin, remaining a friend and collaborator of Lowry Wimberly during these years, reshaped the study of folklore by seeking its living expressions in modern, urban, and socially conflicted settings. Botkin is a national figure, but his Nebraska connections show again the complex bond and mutual influences between Nebraska writers and the Federal Project.

Contact Us

Lincoln City Libraries

136 South 14th Street

Lincoln, NE 68508

402-441-8500