The Nebraska Federal Writers’ Project: Remembering Writers of the 1930s, Part 2D – Writers at Work

From the Union Terminal Warehouse

The purpose of the Nebraska Federal Writers’ Project, as with the Writers’ Project in the other 48 states, was to employ indigent white collar workers to write a State Guidebook and other guides to towns and local culture. When Umland joined the Project in 1936 it had just eight employees; by the end of the year it employed some 57 workers in Lincoln and around the state–unemployed teachers, librarians, college graduates, and newspaper reporters–taken from relief rolls.

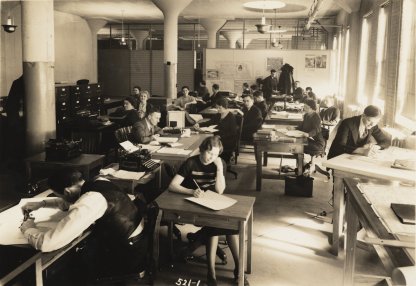

The Lincoln office of the Project shared a noisy railroad warehouse office space just west of the University with several hundred workers from a variety of state and district WPA administrative units. The noise and vibration of the railroad, the clacking of a hundred or so typewriters, ringing telephones, and other activity made writing difficult at first. Still, it was mostly here, Umland reported, that the Nebraska State Guidebook was compiled and edited.

August 1936 photograph of the Nebraska Writers’ Project workspace in the Terminal Warehouse. Rudolph Umland is leaning back at his desk in the row at the right. At the end of the row are Weldon Kees and Jake Gable.

Much of the actual writing was done by the Project’s Lincoln employees. Over a dozen former Prairie Schooner contributors, including Umland, Loren Eiseley, Fred Christianson, Weldon Kees, Jake Gable, Kenetha Thomas, Margaret Lund, Dale Smith, Norris Getty, and Carl Uhlarik, worked in the Lincoln office. Most of the Project’s outstate employees reported on and collected materials on local history and folklore that were forwarded to the Lincoln staff. In some areas of the state the Project could not find qualified workers, and appealed to the schools for information on local history, folklore, and places of interest. This yielded much additional material, enough to keep one of the Lincoln editors busy full time.

In an account of his work editing the WPA Guidebooks published in Prairie Schooner in 1939, Umland recalled some unintended humor encountered in his editorial work. At one time, the State Director, then Elizabeth Sheehan, forwarded to him an account of an early crossing of Nebraska, written by someone in the Lincoln office, with the comment that it was “such beautiful, beautiful writing!” The account gave Umland an editorial nightmare, the traveler was reported to have passed a pleasant evening with locals and then to have set out, against their wishes, to return to his camp in a storm. The manuscript continued,

“Then followed his experiences: he fell into a ravine; he became lost; he saw wolves. When daylight which he awaited came, he tried to reach the Platte River. Here he came upon a hidden glen where were many buffalo bones piled high, a fearful sight. He sang snatches from grand opera and recited all the poetry he knew to pass the night. During the time, he knew no hunger; he had eaten mushrooms and other wild growths. He had great strength, probably aroused by the great strain of fear and hunger. In fact, he wanted to fight a wolf but the wolf would not come out of his den.”

Umland reported that “when I finished reading… I was ready to fight several wolves myself.” The wretched style was due to the inexperience of the writers and the distracting, noisy warehouse environment in which they worked.

Some writers soared into such florid extremes of expression that they had to be let go. One fellow wrote that “We should fill our very souls with the fragrance and beauty” of a Nebraska roadside. This peroration then lit on a grapevine by that same roadside, “let us cast our eye to the roadside. What is on that roadside… Grapevines…” and announced that “California is noted for her raisins but Nebraska too has its possibilities.”

Improvement came with the replacement of the State Director, with Umland’s advancement to Assistant Director, with a move to a quieter downtown office building and with a winnowed and more experienced staff. Umland began to find that the manuscripts crossing his desk were more organized and were based on genuine research. The real work of checking facts, compiling and rewriting and editing was now beginning.

Making Progress

By Federal mandate, the main task of the Nebraska FWP was to research and write a state guide for the American Guide Series. The work could never quite be systematically organized. Some disorganization was due to constantly changing directives from Washington about how to organize the Guide. The intention to make the writing of the Guides a cooperative process that could make use of many different kinds of workers was another source of disorder. In Nebraska, as at the national level, the Federal Writers’ Project evolved, finding new tasks and organizing new ways of working as people at both levels learned more about the job they were doing.

The Nebraska Project employed as researchers many people drawn directly from relief rolls. These workers were chosen for having some college education or previous experience that would prepare them to do the research. Still, they were very inexperienced, and those who worked outstate, in rural areas and small towns, worked on their own without regular supervision. These researchers were temporary workers, the majority of them worked only few months. Nevertheless, as a group they were immensely grateful to be employed in hard times and their enthusiasm for earning their way and gathering information about local history and anything else that might assist the writing of the guide resulted in a flood of raw historical and biographical information. Researchers collected interviews, old settlers’ tales, local folklore, newspaper clippings and other published materials and sent them on to the Lincoln office.

Group portrait of Project employees, with Project Director Jake Gable seated at the right in a dark shirt and tie, Umland standing behind him with a bow tie, Weldon Kees standing just to the left of the map, and Margaret Lund standing to the left in a light blouse.

In Nebraska, as in other states, the flood of information forced editors and administrators to refocus their work. With too much material to include in the State Guide, they decided to develop other publishing projects. These smaller local or topical publications would make more of their materials public, would be good practice for the more demanding job of producing the State Guide itself, and would keep crucial personnel busy while Washington made up its mind about the common framework of the State Guides.

Another consequence of this flood of information was the closing of the outstate offices of the Project in mid-1937. This reflected a Federal hiring freeze, but was also a strategic decision. From then on, information gathering and interviews were undertaken by more experienced personnel.

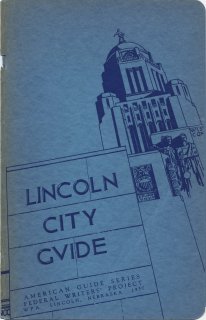

The Lincoln City Guide

As a consequence of these decisions, the very first publication of the Nebraska Federal Writers’ Project was the Lincoln City Guide, appearing in April, 1937. Rudolph Umland described how work on the Lincoln City Guide proceeded in a 1939 article in Prairie Schooner. The work process and the challenges met in publishing the Lincoln City Guide were typical of the Project as a whole.

To begin with, “Old timers were interviewed and newspaper files searched for facts.” Interviews with early settlers, oldest residents, or locally known eyewitnesses to interesting events shaped all of the Nebraska Project’s work on local history. From these interviews came the individual experiences, the local folklore, the interesting differences of opinion, that made it possible for the local guides and then the State Guide to entertain as well as instruct. From these interviews came the ever changing perspectives of an intimate and informed conversation with the reader.

Sometimes the interviews and further research led off in directions that surprised Project workers. Umland noted that most of the workers were women, former school-teachers who, he said, “accepted, in complete seriousness, the assertion that Lincoln was the Bethlehem of America.” Lincoln, which could be said to have become the State’s capital city by stealing the State Seal, various appurtenances, and the State (law) Library from Omaha, actually has a fairly extensive history of financial and moral corruption. Umland found it “a real problem” to get his employees to gather materials that did not conform to Lincoln’s sedate and high minded image of itself.

“Of course,” he added (with Wimberly laughing, “heh! heh! heh!” in the background), “the project was not engaged in compiling such (scandalous) information.” Rather, the editors wanted the Lincoln City Guide to be “unbiased and entertaining.” The editors believed that “the Mollie Hall Cigar Store, a notorious dive of early days, deserved mention as well as the Epworth (Methodist) Assembly.” Each institution, Umland concluded, “contributed to the city’s history.”

The completed Lincoln City Guide anticipates in miniature the organization of the State Guidebook. It begins with brief essays on the natural setting, history, economy, ethnic composition, communications, pastimes and culture of the city. A series of walking and then “motor tours,” noting interesting and important places, buildings and their architecture, businesses, historical venues and city and neighborhood institutions makes up the bulk of the Guide. A timeline and bibliography complete the work.

The Lincoln City Guide offered enduring insights into the social geography and history of the city, and is cited in more recent guides, such as Roger Welsch’s Inside Lincoln, which expresses gratitude to “all of the anonymous writers of the WPA Federal Writers Project.” If it did insist on revealing aspects of Lincoln that some preferred to ignore, it did so in a matter of fact style that seemed to deny intent to either titillate or criticize. Two examples may serve to illustrate this:

The tour of Southwest Lincoln gave this description of the McDonald Mansion at 1510 S. 22nd Street…:

The old house, set back among trees and shrubbery, its lawn surrounded by a high iron fence and the crumbling ruins of an old wall, bears about it an air of gloom and mystery. Originally built…in 1888 by C.T. Brown, grain dealer, it was purchased by Mrs. Annie McDonald, widow of John McDonald, capitalist, in 1912 and lavishly remodeled. The house was named “The Blow” by its mistress [A reference to the sparks that fly when air is blown through a furnace in the making of steel, in the fashionable slang of the day–ed.] , and later “The Hell on the Hill.” Here the most unusual parties in the city were held. These were the topic of conversation among Lincoln circles for years afterward. Mrs. McDonald was fond of horses, and it was a familiar sight to see her in a surrey, accompanied by footman and coachman, driving a span of black horses. Buffalo Bill was often her guest…. In 1920 the first motion picture to be made in Lincoln was filmed on the grounds of the Mansion.

The same tour of the Southwest offered this description of property restrictions in Sheridan Park, Lincoln’s most exclusive residential district.

There is in addition to the clause specifying a $10,000 initial (minimum) cost of buildings erected on the land, a clause stipulating that land shall not be sold to a Negro within 50 years of the transfer of the deed. Because sales are likely to occur within periods of less than 50 years, the restriction is self perpetuating.

When the manuscript for the Lincoln City Guide was completed, the Project looked for a sponsor to publish the work. According to Umland, “A local civic organization was asked… but after several members had read the manuscript, the request was emphatically refused.” The mere mention of the Mollie Hall Cigar Store, and the feeling that the object of the guide should be to glorify the city, not betray its secrets, led to this refusal. In the end, the Nebraska State Historical Society acted as sponsor, and its director, Addison Sheldon, wrote the foreword for the Lincoln City Guide.

Despite the loss of a planned sponsor, a problem that continued to plague other Project publications, the Lincoln City Guide was a great success, the best seller among the local guides. It sold some 16,000 copies at 25 cents each in its first year in print. Local critics and newspapers gave it favorable reviews.

Contact Us

Lincoln City Libraries

136 South 14th Street

Lincoln, NE 68508

402-441-8500