The Nebraska Federal Writers’ Project: Remembering Writers of the 1930s, Part 2F – Weldon Kees and the Writers’ Project

A Biographical Sketch

Weldon Kees (1914-1955) made a reputation as a writer, poet, artist, filmmaker, and musician. Kees was born in Beatrice, Nebraska, and after graduating from Beatrice High School in 1931, attended several colleges. Eventually he came to the University of Nebraska, where he obtained a B.A. in 1935. At Nebraska, he met Lowry Wimberly and published poetry and essays in Prairie Schooner. In 1936-1937 he worked at the Nebraska Writers’ Project.

In late 1937 Kees moved to Denver, Colorado, where he studied library science, worked for the Denver Public Library and served as Acting Director of the Bibliographic Information Center for Research, Rocky Mountain Region. He married Ann Swan, and in 1943 the couple moved to New York, where Kees would write for Paramount News and Time Magazine. Near the end of his stay in New York he served for six months as Art Critic for The Nation.

In 1949 Kees founded Forum 49 in Provincetown, Massachusetts. This group sought to unify artistic genres and included such notables as Hans Hoffman, Robert Motherwell, Adolph Gottlieb and Elaine de Kooning. At the same time, Kees’ own paintings were included in a series of shows at the Peridot Gallery in New York City, and his poetry appeared in respected literary journals and magazines, most notably his Robinson poems in the New Yorker.

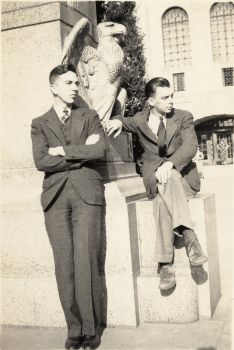

Norris Getty (left) and Weldon Kees at the State Capitol, April, 1937

For work done in this period, Kees is considered an important early figure in the rise of American abstract expressionism. As a writer and critic he was an early champion of the movement. His paintings were exhibited alongside those of Hans Hoffman, Willem de Kooning, and Jackson Pollack. The poetry he was writing at the same time put him in rarefied company, too. The critic Dana Gioia sees Kees as “one of the four or five most talented” members of a generation of poets that included Robert Lowell, Elizabeth Bishop, John Berryman, Randall Jarrell and Theodore Roethke.

Eventually the Kees tired of life in New York and the couple moved to San Francisco, where Weldon entered the film and music scene. He composed music for James Broughton’s avant-garde film “The Adventures of Jimmy” (1951). He collaborated on films with the anthropologist Gregory Bateson, and produced his own experimental films, such as “Hotel Apex.” With his friend Michael Grieg, Kees co-produced both “Behind the Movie Camera,” a weekly radio program for KPFA in Berkeley, and “The Poet’s Follies,” a vaudeville program. In July, 1955, Kees disappeared, leaving his car on the Golden Gate Bridge.

A Wealthy Vagrant

Weldon Kees came to the Writers Project after a series of misadventures away from Lincoln. After he graduated from the University of Nebraska in 1935, he had been accepted at the University of Chicago. He traveled there, but stayed only a few weeks. His biographer, James Reidel, suggests that the prospect of the hard work of graduate school did not appeal to him at all.

He returned to his parent’s home in Beatrice, and then left for Hollywood. A contingent of young people from Beatrice were there to try to capitalize on the success of their former schoolmate Robert Taylor. Kees joined the line, but was rejected. The actor would not even meet with him, probably because Kees had long been advertizing himself as a communist, and with the film industry sharply divided between communists and their opponents, Taylor was a dedicated anti-communist.

Despite the rejection, Kees settled near the studios and made friends with other writers. For a time he had a manuscript for a novel traveling around among New York publishers, and was putting short stories in little magazines. He seemed to be familiarizing himself with the film industry with a view to making a career there. When real opportunity proved elusive, and a fire destroyed some of his manuscripts, he returned to Lincoln.

Kees at the Writers Project

When Kees got back to Lincoln, he learned from his friend Dale Smith that the Nebraska Federal Writers’ Project was offering well-paying jobs to people with the right skills to work on the Nebraska State Guide. Almost all of the administrators and most of the staff, including Smith himself, got their jobs through Lowry Wimberly, and were his former students or contributors to the Schooner. Kees went to see Wimberly.

Wimberly was well enough acquainted with Kees to have some insight into Kees’s character. Kees had published pieces in Prairie Schooner, and had taken a class from Wimberly in his senior year at Nebraska. Wimberly, James Reidell tells us, had “watched …[Kees] drink beer and talk like a communist at the Bull’s Head.” Wimberly had helped get Kees into graduate school at the University of Chicago, and knew Kees had abandoned that opportunity. He probably knew much about Kees futile stay in Hollywood, too. Kees cordially detested Wimberly, who he thought of as a stuffed shirt, “a still-born dilettante and … provincial academic,” (James Reidell) and Wimberly undoubtedly knew Kees’s opinion of him, too.

So it was with a twinkle in his eye that Wimberly reached for the phone, called Jake Gable, Director of the Project, and recommended Kees for a job. He sent Kees directly over to the Terminal Warehouse. Kees met with Gable and was, then and there, hired to work on the Guide and shown to a desk. Wimberly sent Kees to the Project because he knew Kees was a gifted writer who might contribute something to its success. He also sent him because he knew that Kees was rootless, and for all his intellectual sophistication, vastly inexperienced. Wimberly believed it might do Kees some good to learn something about his Midwestern heritage, and that Kees might learn much from just having a job and having to work with others. Experience might blunt Kees cynicism and convert his ideological posturing into something more fruitful. He sent Kees to the Project then, as an experiment. It would be interesting to see how Kees got along.

Kees job at the Guide brought him into close contact with Rudolph Umland. The two men developed a cordial initial acquaintance, probably due mostly to Umland’s curiosity and diplomatic skill. The two men were, however, so far apart in temperament and experience that each was bound to have moments of antipathy for the other. Kees was the son of a wealthy Beatrice factory owner. “I suspect that Weldon Kees was wholly dependent on his parents from the time of his birth until he worked on the WPA Writers’ Project,” Umland later wrote. Umland, on the other hand, had been a hard-working Nebraska farm boy, and worked at many different jobs in his traveling years. This contrast in experience might have been a source of friction between the two men. Yet Umland, like his patron Wimberly, was quite capable of admiring a writer, regardless of other judgments he might make about the person doing the writing. Kees often condescended to Umland, whom he came to regard as provincial and as an ideological reprobate.

Umland first met Kees in April 1936, several months before Kees got a job at the Project. Umland had read some of Kees’s short stories in the Prairie Schooner, and liked them. The two struck up an acquaintance:

Weldon seemed to have a romantic streak in him at that time. One day we met some girls and he was smitten by one of them. He wanted to sleep on the lawn beneath the girl’s apartment that night and coaxed me to accompany him. It was a starry spring night and he talked about girls, playing in dance bands, stories he had written, and books he had read with boyish enthusiasm. About 3 a.m. I left him there on the grass and went back to my own furnished room. I was 28 and unmarried then; Weldon was six years younger.

When Kees arrived at the Nebraska Writers’ Project, Umland was already editor-in-chief of the Nebraska guidebook. Umland assigned Kees writing and research work on the guidebook materials, but found Kees to be “handicapped by a lack of knowledge of Nebraska history and a lack of interest in history.” Kees's cast of mind was oblivious to the past and frantic to find the future.

The writers project work about Nebraska pioneers bored him, irritated him. He had a brain that couldn’t go back into the past. He snickered and sneered at the work we were doing. He was a likeable but sometimes obnoxious youngster with a perverted sense of humor that frequently sent him into a paroxysm of laughter. He was a spoiled and brilliant adolescent who had read much about art, poetry, and the movies and remembered everything he had read about those subjects. He had never done a day’s work for wages in his life and had never needed to. He was friendly and nice to your face but vicious and cutting in his remarks when you turned your back. I can’t say that he ever contributed a single sentence to the Nebraska state guidebook or the Lincoln City Guide. And if he re-wrote any of the texts I for one didn’t know about it.

After four or five months of trying to get Kees to do some work on the guidebooks, Umland gave up and turned him over to Project Director J. Harris Gable “who had a few other ‘talented’ persons and charity cases under his supervision.”

While they were employed by the Writers Project, Weldon Kees, Norris Getty and Dale Smith became close friends and traveled about together. Jake Gable “called them ‘the unholy trio.'” The three “went into gales of laughter at circumstances that were inappropriate for merriment.”

One day on a Lincoln street the trio encountered a woman whipping her little boy. “Hit him again, Ma’am!” Weldon shouted jumping up and down gleefully. “Beat him with a stick until his teeth falls out! He’s just a little fellow who can’t hurt you!”

Umland called this same trio the “parlor pinks,” for their unworldly, but very self-conscious and voguish espousal of communism. Letters (here and here) that Weldon Kees wrote to Dale Smith about the time Kees departed the Project give some idea of the spirit of the group. No one has ever suggested that Kees had ever read Marx or actually knew much about communism, it was all as far from his ken as the struggles of Nebraska’s early settlers. At a time when the Depression had undermined the legitimacy of the social order, it was a popular style of self-presentation for young intellectuals, and Kees liked to be in style. In the 1950s, Mari Sandoz told Umland that she met Kees when he was living in New York and found “he had exchanged his communist philosophy for one almost fascist in nature.”

While Kees’s habit of replying “Nonsense, Rudy!” to any comment or suggestion he would make irritated Umland, the two continued to meet socially and talk about writers and writing. On various occasions in 1936-1937 Weldon Kees’ father would drive to Lincoln to visit with his son. Sometimes Lowry Wimberly, John and Weldon Kees, and Rudy Umland would spend an evening over a couple of beers at the Bull Head Tavern on N Street. The father hoped his son would develop an interest in his manufacturing business, but that was not to be.

Perhaps it was after such a meeting that Lowry Wimberly suggested to Umland that maybe Weldon Kees represented the appearance of an entirely new type of person on the face of the earth, “one whose mind might be forever fixed in the present and the future.”

The past might be discarded altogether and all morals of the human race perish. The most amusing thing Wimberly could envision was the population of the city suddenly without clothes–men, women and children walking and scurrying along the streets, going about their work stark naked and unconscious of the fact.

Wimberly and Umland could laugh at this picture of buttoned-up Lincolnites unaware of their humiliation, but recognized it as a vision of how people might lose their dignity as human beings but lack the perspective to recognize their loss. Impatience for the future is a mindset that abandons real achievements for an ever changing mirage of what might be. Looking back at the world from that mirage, the chimeras and demons of the imagination will come to bitterly despise all that is real, for they cannot cross to the other side and live again in the world.

After Kees’s suicide, Umland recalled what Wimberly, Loren Eiseley and Weldon Kees had all seemed to have in common. They feared, he thought, the dehumanized mankind that each of them perceived looming in the future. The human mind needs light from outside to guide it; without this spirituality, or without a soul to perceive the light, human life is meaningless. The aggrandizement of the human mind is a journey toward blindness. Wimberly and Eiseley wrestled with this problem at a more mature age, and their despair was tempered by scholarship and cultural commitment. Umland observed that Weldon Kees stared into nothingness at a much earlier age, and grew too dispirited to escape its vortex.

Umland recalled that in early 1937, a friend had lent him a copy of Phillip Horton’s biography of Hart Crane, and Kees, visiting Umland’s apartment, saw it and asked to borrow it. “He was deeply impressed by the book and talked about Crane’s troubled life for days.” Kees spoke of his own mother with much hostility. Art Bukin, a Project writer, accompanied Kees on a visit to Kees’s parents home in Beatrice. Kees evidently had little to say to his parents by way of greeting. “Weldon went immediately to the piano and started thumping away on the keys. He played a dance tune very loudly.”

Umland also remembered that Kees grew increasingly bitter, resentful, and ideological in the months before he left Lincoln. “Sometime during his last months in Lincoln I suspect he became convinced he was a rare genius and fell in love with himself.” He associated more and more only with Norris Getty and Dale Smith, who shared all his opinions. This transformation appeared to be a lasting one. Kees now turned away from writing stories, to poetry, and critics call his poetry some of the most bitter in the English language. In 1947 or 1948 Kees sent Lowry Wimberly a poem with a note “For Umland–WPA–Remember?” scrawled at the top. The poem appeared in Kees’ Collected Poems with the title “The Older Programs That We Falsified.” For Kees everything was false, the poem was another bitter gesture, with a touch of ‘holier than thou’ added in the title just for effect.

In 1956, the year after Kees disappeared, Rudolph Umland had a dream about him and told Wimberly about it.

I dreamt that I was swimming underwater amid seaweed, small fish, and strange acquatic plants when I suddenly saw the white, nude corpse of Weldon. The eyes flicked open, a hand fluttered a greeting, and words started issuing from the lips. I couldn’t distinguish the words and swam nearer and shouted at Weldon to speak louder. He drew his lips down in a mournful grin, shook his head, and said, “It’s all nonsense, Rudy, all just nonsense.” A knowing look came into Wimberly’s eyes when I told him the dream, and it muttered, “Well, that’s about it, just nonsense.” Meaning human existence, I guess.

The English poet Milton leaves it to Satan to tell us, defiant at his defeat, that “The mind is its own place,” and can make a hell out of heaven or a heaven out of hell. Many modern writers and poets have felt the seductive power of this vision, and its terror and futility. The best among them have tried to preserve kinds of commitment and accountability that disprove it, even in the face of technical progress that seems to allow human beings to reshape more and more of the world at a whim. Wimberly and Umland tried very hard to show Kees that a healthy mind needs a place outside itself and to push him toward his Midwestern heritage. He resisted them quite successfully.

Umland could not help but admire Kees as a writer, he especially liked Kees’s early short stories, and recognized the power of his poetry. Yet he judged Kees the suicide rather harshly:

Kees was an aesthete and might have been happier had he been born somewhere other than the American Midwest. He was a romantic however much he despised that word. He treated his life as an art object and wanted to be a universal man like Goethe or Humboldt. He tried to be a great fiction-writer, a great poet, a great jazz musician, a great painter, a great photographer, a great movie-maker, a great critic. He tried to attain greatness in all these things but did not try hard enough or long enough. He finally decided that killing himself was the next best thing to being great. At least success in that could come quickly. Kees was always filled by a great impatience.

Contact Us

Lincoln City Libraries

136 South 14th Street

Lincoln, NE 68508

402-441-8500