The Nebraska Federal Writers’ Project: Remembering Writers of the 1930s, Part 2G – Loren Eiseley and the Federal Writers’ Project in Nebraska

One of the Nebraska Writers’ Project’s early employees was Nebraskan Loren Eiseley (1907-1977). Eiseley would make his career as an anthropologist, teaching for many years at the University of Pennsylvania. Eiseley was a powerful essayist who gained an ever widening audience for his ability to show us what our investigations of the natural world reveal about human insight and human limitations. In time, beginning with the publication of The Immense Journey in 1957, Eiseley would make himself one of the most widely read and highly regarded nature writers of the twentieth century. His writing gained him admirers and correspondents as diverse as the science fiction writer Ray Bradbury, the poet W.H. Auden, and the cultural critic Lewis Mumford.

Rudolph Umland was already working for the WPA when he met Loren Eiseley for the first time in 1936. Eiseley, on loan from the National Youth Administration, came to work for the Writers’ Project, and fell into the habit of visiting Umland in his living quarters, a furnished room at 510 South 18th Street in Lincoln. “When I met Loren in January, 1936 we had instant rapport,” Umland recalled. The two had heard about each other for a decade. Eiseley, as a student editor at Prairie Schooner had actually read portions of Umland’s book manuscript about his experiences as a hobo from 1928-1931. Wimberly had passed part of the manuscript to Eiseley to select parts for publication in the Schooner. Umland, in turn, had read two of Eiseley’s own sketches of hobo life in the Schooner. Umland thought that they might talk about the challenges of hobo life, but found that Eiseley did not want to talk about it. “I think Loren must have suffered more intensely because he didn’t seem to want to recall his experiences.” “He seemed so hesitant and vague and uncertain that we were soon talking about other matters.”

Loren Eiseley, early 1936, on loan to the Writers’ Project from the National Youth Administration

Eiseley kept questioning Umland about his plans for the future. At some point, Umland told Eiseley that he himself had no intention of ever returning to the University to obtain a degree. Eiseley was shocked and dismayed. “The WPA would end one day!” What would Umland do then?

In these and other conversations, Umland discovered “a sense of insecurity that puzzled me.” Eiseley had obvious gifts, but “showed little confidence in his ability to ever earn a living.”

Umland knew Eiseley’s friends and teachers, had heard them talk about Eiseley, and had seen them point him out crossing the University campus, long before meeting him. Umland had known Mabel Langdon, Eiseley’s future wife, since 1927, when she helped him change his registration from the College of Engineering to the School of Fine Arts. Interested in Eiseley from the beginning, Umland was an acute observer of Eiseley as a man and as a writer. Umland’s own curiosity and gregarious nature brought him interesting tidbits of Lincoln gossip that broadened his understanding of Eiseley’s world.

Umland admired his friend and came to recognize his genius. As the Nebraska Guide took shape it was Eiseley that Umland assigned to write the chapters on the State’s natural setting and prehistory. His admiration for Eiseley the writer grew in later years as Eiseley began to publish his essays. Many of Eiseley’s essays about science and its implications are inspired by fragments of autobiography. When Eiseley finally wrote a longer autobiography, it belonged to the same genre as his essays, it offered up nothing personal, no narrative of family life or career. Instead, the book offered “an excavation” of Eiseley’s inner life of the mind, in which autobiographical details were discrete and disconnected, used only to spark a more philosophical inner dialogue.

Over the years, as a reader who knew Eiseley, Umland tried to puzzle out how much of that autobiographical detail was accurate and how much arose from Eiseley’s illusions or perhaps, authorial license.

We owe much of what we know about Eiseley’s milieu and his Lincoln years, especially the 1930s, to Umland and to Eiseley’s biographer Gale Christianson. Christianson’s inquiries rekindled Umland’s memories of Eiseley, and induced him to record them on paper. In their correspondence and conversations, Christianson and Umland tried to piece together the autobiographical fragments in Eiseley’s books with what they knew about his real life. The two pictures did not always correspond. Christianson’s 1990 Fox at the Wood’s Edge: A Biography of Loren Eiseley showed Eiseley to have been a complex man, whose writing was often inspired by personal vulnerabilities, frailties and defects that he wanted, at the same time, to conceal. Although Eiseley’s character, defects included, was surprisingly well understood in 1930s Lincoln, he was, as “one of our own,” an insider, quite strikingly well liked and highly regarded as a promising young writer.

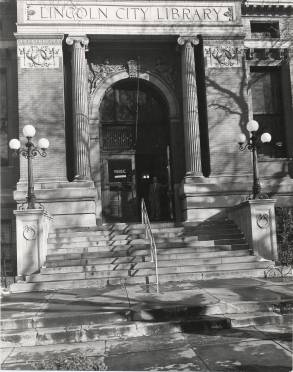

Entrance to the Lincoln Library in the 1930s. The door to Eiseley’s world.

Eiseley, Umland reported, tried to leave home on various occasions, but having difficulty fending for himself, he “returned to read more books and scribble more verses.” Eiseley’s very evident sense of insecurity was probably a consequence of his poetic dreaminess. “Most boys growing up in Lincoln got their first work experience mowing lawns, delivering newspapers, washing windows, scrubbing floors, hoeing weeds, spading gardens but Loren did none of these things.”

From the time he was a teenager his mother had been constantly after him to find part-time work but he would hole up in the City Library and read books instead of making an earnest search. He read science fiction, the poets, the nature writers, ghost stories. Librarian Lula Horn said he had to be chased out of the stacks at closing time. He read pulp magazines too and read through stacks of Railroad Stories that his father brought home. He didn’t like to go begging for a job from strangers. A family friend finally secured the chance for him to work in the chicken hatchery. Aside from summer digs, cleaning bones in the museum and posing for art students this hatchery work was his only employment prior to the WPA Writers’ Project. He was 28 years old then.

Umland came to believe that Eiseley was a victim of his own “prolonged adolescence,” so that “as he approached maturity he seemed actually fearful of making his own way in the world.” Believing that the world was divided into “two kinds of living things–the hunters and the hunted,” Eiseley came to see himself as “one of the hunted.” He saw himself as “a fugitive, a Steppenwolf figure.”

This image became an accompaniment to his poetry-writing. It persisted and grew to blossom strangely in the books he wrote.

He made up images “to conceal his anxious self, and he called it ‘symbolical writing.'” Umland pointed to Eiseley’s “startling picture of himself as prisoner of a Mexican guerrilla with submachine gun” in The Immense Journey as an example of these fictions.

Eiseley made much of his travels as a hobo in his writing. But with his sensitive temperament and lack of real world work experience, Umland did not think Eiseley would have lasted very long hopping freights and working as an itinerant laborer. “He had too much pride to beg for dimes and was too inexperienced and helpless… to make it as a transient laborer.”

Eiseley had never “shocked wheat, operated a binder, picked corn, rode fence, castrated pigs, milked a cow, picked fruit, washed dishes in a hash joint, beat rugs or done any of the other odd jobs that a hobo must occasionally do…”

A hobo has to do a bit of scrounging now and then to stay respectable. He has to hold up his own end and not expect others to do his scrounging for him. Loren was all Intellect, all Abstraction. He could not have survived a long period of ‘drifting.’

Umland believed that the longest period that Eiseley actually spent on the road was a week or ten days in August or September of 1930. His mother being unable or unwilling to send him money, Loren had to make his way back to Lincoln from California on his own.

Umland recalled:

He arrived back ‘in a terrible state,’ according to Mrs. C.R. Hasskarl… who was secretary to Prof. R.J. Pool of the Botany Department at the University. He was emaciated and his eyes were sunk in his head. He had no money and Viola (Mrs. Hasskarl) and Mabel Langdon bought him meals and Mabel took him in tow and got him back into school and eventually made a famous man out of him. I think it was Viola Hasskarl who said that Mabel should be the heroine in any biography written of Loren. I don’t believe Loren could have spent more than six weeks altogether in his life as a hobo. I suppose to him, thinking back on it, it seemed years.

When he read one of Eiseley’s literary descriptions of his experiences as a train-hopping hobo, riding on top of the rail cars, Umland laughed: “Think of it! Tying yourself by the wrist to the catwalk and spending the night that way. Not only Loren but scores of fellow hobos crazy enough to do a thing like that as related [on page 9 of All the Strange Hours]. What a sight they must have presented rising from the roofs of that long drag of freight cars to greet the morning sun.”

Umland continues:

I can’t believe it. Hobos have common sense like most people. Were readers intended to believe it or merely to accept it as permissible literary exaggeration? What kind of obsession did Loren have about riding on the roofs of cars? Hobos crawling over the roofs. Hobos creeping off the roofs. Brakemen running down the roofs. I can’t remember ever seeing a hobo on the roof of a car except temporarily. Loren evidently came to regard only inner facts as facts and things that were real outside as opportunities for parables…. I think he was embellishing his hobo experiences to make them something different, something symbolic, something stylized, something unforgettable in the …[strange] Eiseley way he had.

When Eiseley projected himself as a tough guy, Umland could not square that image with the Eiseley he knew. “The one I see is cautious, anxious, uncertain, terrified, somewhat frail.” Perhaps Eiseley was writing about the sort of person he wanted to be. But it often seemed more complicated than that: “Loren often seemed to be feeling another person in him, a primitive person from a past age. (Maybe such a person really existed in him?)”

Umland was beginning to recognize Eiseley’s deep sense of vulnerability and something of the multilayered, complex personality that Eiseley constructed to protect that vulnerability. Eiseley’s tendency to adopt disguises would be clearer later on. Here after all, was a poet who became a scientist, in order to pursue a writing career. Here was an anthropologist, who wrote much about his thoughts in the field, who in fact only spent a few seasons there, and most of those only at the very beginning of his career. Eiseley’s literary ambition was far more compelling to him than any purely scientific interest, but once he began his career as a scientist, he kept that ambition hidden until he was secure.

Eiseley, with a deaf and mentally disturbed mother and an often absent father, had a lonely and unhappy childhood that led him to seek refuge in nature. Encouraged to read and take an interest in literature by his rather perceptive father, he took refuge in books as well. From the time that Lula Horn began to have to chase Eiseley out of the Lincoln City Library at closing, people knew the Eiseley boy seemed to live in his own head. Wimberly told Umland that Loren had been isolated by a writer’s conciousness since early childhood.

So aware of Eiseley’s foibles was Lincoln society that when Eiseley told Wimberly that he was thinking of marrying Mabel Langdon, an attractive and intelligent young woman who was greatly respected for her work in building the art department at the University and in improving the University Museum’s art collection, Wimberly tried to dissuade him. Eiseley, he knew, was financially dependent on others (including, already, Mabel Langdon, a fact Wimberly probably did not know), moody, melancholic, a loner, an escape artist who hardly seemed a suitable match for the somewhat frail, but very sociable and accomplished aristocrat. Umland observed that this conversation altered the friendship between the two men. Eiseley and Wimberly had been very close, and did remain friends. But the friendship was cooler, and Eiseley the writer, Umland thought, owed an intellectual debt to Wimberly that he could not bring himself to acknowledge in later years.

Umland’s intuition of that debt (he never quite spelled it out clearly) has several elements. Wimberly mistrusted, as we have seen earlier, the way science attacks older, alternative cultural traditions that contain much human experience and wisdom. Eiseley too had a lively understanding of the limitations of science. “I have given the record of what one man thought as he pursued research and pressed his hands against the confining walls of the scientific method,” he wrote. Eiseley sought to show his readers how it is spiritually necessary for human beings to view scientific facts from perspectives beyond science if we are to understand the power and limitations of what science gives us, and our responsibility for the world we create.

When Umland picked up Eiseley’s The Firmament of Time, he was once again reminded of the connections between Wimberly, Eiseley and Weldon Kees. Eiseley, he said, wrote as “a poet-naturalist trying to attach some meaning to human life:

Since antiquity man has searched for such meaning outside himself. Looking back across the centuries, Loren said, toward the animal men of the past, one sees a faint light, like a patch of sunlight moving over the dark shadows on a forest floor. It is the human spirit, the human soul, however transient, however faulty men may claim it to be. Without this light man is nothing, and his place is nothing. Even as we try to deny the light, we know that it made us, and what we are without it remains meaningless. Like Wimberly, Loren feared the dehumanized man looming in the future. In the end man might become all mind having no light, Loren wrote—-no spirituality, to guide him further. He might not see himself as part of a flowing stream but only as an entity. Why continue the farce? Wasn’t that what Wimberly had been fearful of all along? Wasn’t that the nothingness Weldon Kees had glimpsed? In the end the different sets of patterns envisioned by Kees, Eiseley and Wimberly had all fused together. After probing to uncover the secret of their individual existences, and finding it, they had sought to scratch the dirt over it again. But Kees hadn’t scratched the dirt long…

Despite their awareness of Eiseley’s scars and frailties, Wimberly and Umland held Eiseley in high regard and showed considerable affection for him. Umland’s comments hint that this was not all due to his skill as a writer, or memories of long evening conversations in Wyuka Cemetery, but to a sense of a deeper connection arising from some shared perceptions of the spiritual problems of modern life.

Eiseley invented a literary genre or form all his own, the “concealed essay,” he called it, that used intensely personal experience to reflect on nature, the universe that science uncovers but whose meaning it cannot elucidate, and man’s place in that universe. He seemed to have the essayist’s and poet’s conviction that it is neccessary to feel the facts, that to sustain an objective, external view of nature for too long will cloud our understanding and induce, in the belief that we are separate from nature, arrogance and hubris. We invent our own experience of the world, and to know itself the human mind must recognize its own complete immersion in historicity and change. In the recognition of our own loneliness and the fragility of our vision, Eiseley seemed to think, we might find the capacity to make choices that recognize and redeem a world we hold in common with our fellow creatures, a world we can also destroy.

What might interest us most here is the tone of this work. The sense of loneliness, isolation and melancholy are familiar themes of Plains literature, reflecting the sparseness of human settlement and way geographic distances intrude on human relationships. Eiseley brings these into an inward world. He evokes ancient landscapes, and they are, almost always, Plains landscapes. He understands–as perhaps a writer from no other region could–that nature may be at once imposing, terrifying in its power, and infinitely fragile. On the Great Plains, more, it seems to us, than elsewhere, harsh sunlight, wind, powerful storms, open space and vast distances mock and overwhelm human efforts at permanence. Eiseley’s vision of the absolute historicity of the mind echoes human experience of the Plains environment. Should we think of Eiseley as a regional writer? Surely not, but the kinship seems unmistakable.

“Of the group of Lincoln writers who emerged from the Wimberly years,” Rudolph Umland thought, “Loren was unquestionably the most intellectual, the most profound.” Some of Eiseley’s essays would “belong among the great essays of literature.” Eiseley’s first published poem, appearing in the Schooner in 1927, already revealed–Umland believed–a unique and unusual quality of mind.

Contact Us

Lincoln City Libraries

136 South 14th Street

Lincoln, NE 68508

402-441-8500